Russian empire map

Содержание:

Military, finance, and administration

By 1710 Russia had a regular army recruited by conscription from among the peasantry and petty townsfolk, the first of its kind in Europe. In 1724 its effectives numbered 131,400 infantry and 38,400 cavalry, excellently trained and equipped. The Black Sea fleet had to be given up, together with Azov, in 1711. The Caspian flotilla was used against Persia in 1722. The Baltic fleet, built mostly in Russia after 1700, consisted in 1711 of 11 ships of the line (increased to 44 by 1724) and frigates armed with over 200 guns and manned by some 16,000 sailors. The cost of the army, 4 million rubles annually, was the chief item in Russia’s budget.

After 1718, when the poll tax was first introduced, the deficit was gradually reduced until in 1724 a surplus was obtained. Financial and administrative reform went hand in hand. The kollegii (colleges)—central administrative departments—established between 1718 and 1722 were severally concerned with war, the navy, foreign affairs, foreign trade, state revenue, state expenditure, audit, justice, mines, factories, spiritual affairs, the estates of the gentry, and “Little Russia” (modern Ukraine). Fifty provintsii (provinces), each under a voyevoda (chief), were subordinated in part to the colleges and in part to the senate. Established in 1711, when it replaced the council of ministers that had evolved from the boyar duma, the senate became a superior authority whose task it was to control and coordinate all the organs of government, including the secret police. The senate in turn was supervised by a procurator, Russia’s all-powerful chief bureaucrat, from 1722 responsible to the emperor only.

Administrative reforms

After the emancipation of the peasants, the complete reform of local government was necessary. It was accomplished by the law of January 13 (January 1, Old Style), 1864, which introduced the district and provincial zemstvos (county councils). Land proprietors held a relative majority in these assemblies. The gentry and officials were given (in all Russia) 42 percent of the seats, merchants and others 20 percent, while the peasants had the remaining 38 percent. The competence of zemstvos included roads, hospitals, food, education, medical and veterinary service, and public welfare in general. Before the end of the century services in provinces with zemstvo government were far ahead of those in provinces without.

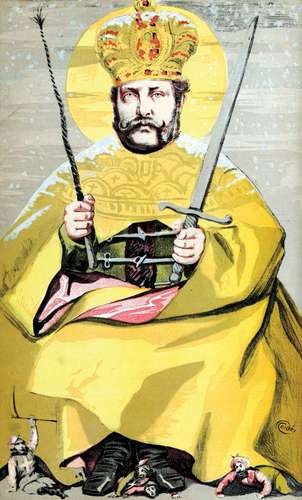

Alexander II, illustration by James Tissot for Vanity Fair, October 1869. Photos.com/Thinkstock

A third capital reform touched the law courts. The law of December 2 (November 20, Old Style), 1864, put an end to secret procedure, venality, and dependence on the government. Russia received an independent court and trial by jury. The judges were irremovable; trials were held in public with oral procedure and trained advocates. Appeals to the senate could take place only in case of irregularities in procedure.

Later came the reforms of municipal self-government (1870) and of the army (1874). Gen. Dmitry Alekseyevich, Count Milyutin (the brother of Emancipation Manifesto framer Nikolay Alekseyevich Milyutin) reduced the years of active service from 25, first to 15 and then, by the law of 1874, to 6 years, and made military service obligatory for all classes. The term of service was further shortened for holders of school diplomas. Military courts and military schools were humanized.

Emancipation of the serfs

The greatest achievement of the era was the liberation of peasants. It paved the way for all other reforms and made them necessary. It also determined the line of future development of Russia. Alexander’s chief motive is clearly expressed in his words to the Moscow gentry: “The present position cannot last, and it is better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait till it begins to be abolished from below.” Alexander knew, of course, of the mounting dissatisfaction of the peasants and of support of their grievances by the progressive intelligentsia. However, he met with passive opposition from the majority of the gentry, whose very existence as a class was menaced.

The preparatory discussion lasted from 1857 to March 1859, when the drafting commissions of the main committee were formed. These young officials were enthusiastically devoted to the work of liberation. Iakov Ivanovich Rostovtsev, an honest but unskilled negotiator enjoying the full confidence of the emperor, was mediator. The program of emancipation was very moderate at the beginning, but was gradually extended, partly under the influence of the radical press and especially Aleksandr Herzen’s Kolokol (“The Bell”). Alexander wanted the initiative to belong to the gentry. He exerted his personal influence to persuade reluctant landowners to open committees in all the provinces, while promising to admit their delegates to discussion of the draft law in St. Petersburg. No fewer than 46 provincial committees comprising 1,366 representatives of noble proprietors were at work during 18 months preparing their own drafts for emancipation. They held to the initial program, which was in contradiction with the more developed one. The delegates from the provincial committees were only permitted—each separately—to offer their opinions before the drafting committees.

By the Emancipation Manifesto of March 3 (February 19, Old Style), 1861, the peasants became personally but formally free, and their landlords were obliged to grant them their plot for a fixed rent with the possibility of redeeming it at a price to be mutually agreed upon. The peasants remained “temporarily bonded” until they redeemed their allotments. The redemption price was calculated on the basis of all payments received by the landlord from the peasants before the reform. If the peasant desired to redeem a plot, the government paid at once to the landowner the whole price (in 5 percent bonds), which the peasant had to repay to the exchequer in 49 years. Although the government bonds fell to 77 percent and purchase was made voluntary, the great majority of landowners—often in debt—preferred to get the money at once and to end relations which had become insupportable. By 1880, 15 percent of the peasants had not made use of the redemption scheme, and in 1881 it was declared obligatory. The landowners tried, but in vain, to keep their power in local administration. The liberated peasants were organized in village communities that held comprehensive powers over their members. Nominally governed by elected elders, they were actually administered by crown administrative and police officials.

TAG | Russian Empire

Dec/18

7

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in History, People, Photos

The following photos were taken by an unknown person belonging to the so-called Czechoslovak Legion, which stuck in Russia after the revolutionary events of 1917 and played an important role during the Russian Civil War. Source: humus

1. Small person guiding a blind one

Tags: Russian Empire

Sep/18

8

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in Architecture, History

This album of projects of urban and rural buildings of the Russian Empire was compiled by the engineer-architect V.G.Zalessky with the participation of a number of other engineers and architects in 1881 – a very interesting document of its time with beautiful illustrations. Source: humus.

Tags: Russian Empire

Apr/18

3

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in History, People, Photos

The second set of photos of common people taken by William Carrick (1827-1878), a Scottish-Russian artist and photographer, in the Russian Empire. The first part. Source: humus.

1. Orthodox priest.

Tags: Russian Empire

Mar/18

21

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in History, People, Photos

William Carrick (1827-1878) was a Scottish-Russian artist and photographer. In 1859, in St. Petersburg, he opened the first photo studio in the Russian Empire.

Carrick quickly gained fame, capturing the daily life of the country and became the first Russian ethnographer-photographer. Let’s look at some of his works. The second part. Source: humus.

Musician playing a balalaika.

Tags: Russian Empire

Feb/18

23

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in Art, Culture, Nature

Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin (1832-1898) was one of the greatest Russian landscape painters, who created very photorealistic pictures.

In his paintings he depicted the nature of the middle part of the East European Plain also known as Russian Plain, one of the largest plains in the world.

Rye (1878).

Tags: Russian Empire

Feb/18

5

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in Art, Entertainment, History

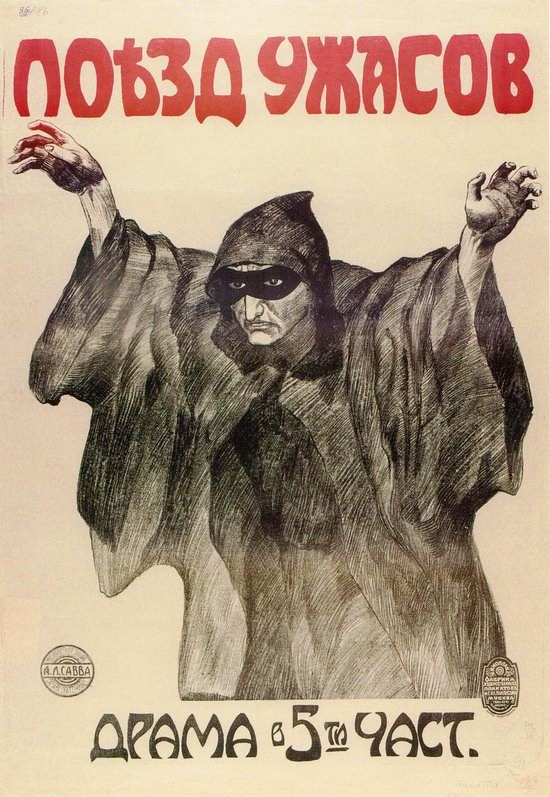

In 1913, on the wave of the general rise of the Russian economy, the rapid growth of the cinematographic industry began in the Russian Empire. In 1913, according to incomplete data, there were 1,412 movie theaters in the country, of which 134 – in St. Petersburg and 67 – in Moscow.

The heyday of the artistic Russian cinematography occurred during the First World War. In 1916, at least 150 million tickets to movie theaters were sold in the Russian Empire. Let’s look at the movie posters of these times. Source: humus.

1. Train of Horrors (1910s).

Tags: posters · Russian Empire

Feb/17

10

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in History, Photos

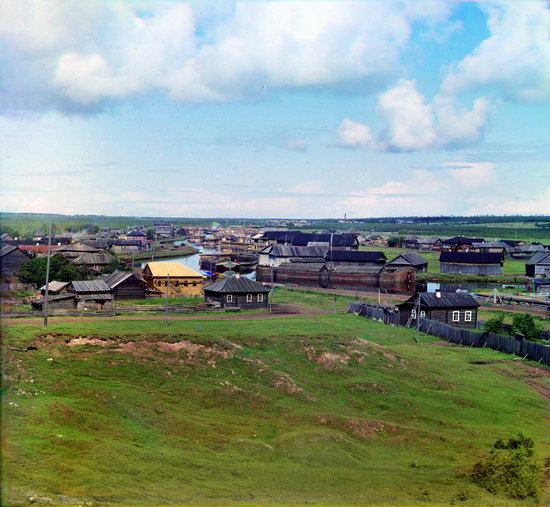

Today, Vytegra is a small town (since 1773) with a population of about 10,000 people standing on the banks of the Vytegra River, 337 km north-west of Vologda, in the Vologda region.

You can see how this place looked like 108 years ago, in 1909. It is possible due to unique color photographs made by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky. Source.

General view of Vytegra and the Vytegra River.

Tags: Russian Empire · Vologda oblast

Feb/16

28

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in History, Photos

Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky (1863-1944) was a Russian photographer, chemist, and inventor, who made a significant contribution to the development of photography and cinematography and was a pioneer of color photography in Russia.

In 1909-1916, Prokudin-Gorsky traveled a large part of the Russian Empire, photographing ancient churches, monasteries, factories, towns, villages, and a variety of domestic scenes.

The town of Zubtsova on the Volga River (1910).

Tags: Russian Empire

Nov/15

4

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in History, Travel

The Alexander Palace is one of the imperial palaces of Tsarskoye Selo (today, the town of Pushkin, part of St. Petersburg), located in the northern part of the Alexander Park. The palace was built by order of Empress Catherine II in 1792-1796.

At the beginning of the 20th century, during the reign of Nicholas II, the Alexander Palace became the main residence of the imperial family and the center of court life. Photos by: deletant.

Tags: Russian Empire · Saint Petersburg city

Oct/15

16

·

Posted by Sergei Rzhevsky in Architecture, Entertainment, History

“The motives of Russian architecture” was a magazine published from 1873 to 1880. The magazine showed drafts and sketches of houses, public buildings created by the followers of the so-called “Russian style” in the architecture.

This style, based on the traditions of folk culture, revived the old methods and motives of Russian architecture. Country houses, exhibition halls, public buildings, churches looked like magical houses of Russian folk tales. It was thought that these projects were desirable to build all over Russia. Pictures by: humus.

Tags: Russian Empire

Page 1 of 31

Church and education

In 1721 Peter abolished the Moscow patriarchate, and the Russian Orthodox Church was subordinated to the state through the Holy Governing Synod, a ministry of ecclesiastical affairs under the direction of a lay chief procurator. The church—in 1722 the landlord of about 1 million peasant families—was nationalized also in the economic sense: the income from its lands was passed on to the state. Thus the policy of control and financial exploitation applied to the church since 1696 became a fundamental law. The church was also called upon to establish diocesan schools for the sons of clergy, in addition to maintaining the two ecclesiastical academies already in existence in Moscow and Kiev.

Lay education owed its expansion to naval and military needs. In 1701 a navigation school was established, the first of four, and in 1715 a naval academy for 300 pupils to provide in Russia the training for which hundreds of young dvoriane previously had been sent abroad. Basic knowledge of reading, writing, and mathematics was compulsory for sons of the gentry, for whom the provincial “cipher” or elementary schools established in 1714 were primarily intended. The engineering school prepared pupils for the so-called Engineering Company created in 1719. The Moscow teaching hospital was established in 1707, and a secular academy was decreed in 1724.

Internal disturbances

The new Russia, secular and westward-looking, grounded on a standing army and a tax-gathering bureaucracy, also had its internal enemies. In 1705–06 the populace of Astrakhan (one of the principal trading centres with the Middle East) overthrew the government of Boris Alekseyevich Golitsyn. In 1707–08, on the Don, runaway serfs, deserters, and conscripted labourers under Kondraty Bulavin, a Cossack ataman (hetman), rose up in arms against the boyars and chiefs, foreigners and tax collectors, and the official church. Between 1704–06 and 1720–25 hungry peasants rioted against conscription and taxation. The secret police and punitive military expeditions stamped out all opposition to Peter’s government.

About Us

Russian Empire DMC is a professional services company that can organize any type of local events and activities and design tailor-made programs and tours for any number of participants. It is a dynamically developing company which was set up by professionals with more than 12 years’ experience of working in the tourism industry.

We are happy to make your stay and experience in Russia bright and memorable!

Let our creative and hearty company manage your meeting or event!

Welcome to Russia with Russian Empire Destination Management Company!

What we Do

Meeting and Conference

Meeting and Conference

Russia is ideally situated as a destination for all types of business events with its unique facilities, world-class dining, natural beauty and famous attractions.

Learn More

Incentives

Incentives

Incentive travel has grown in recent years as corporate motivational and marketing tool. Incentive travel programs not only keep employees happy, they also push up your brand image.

Learn More

Events

Events

Looking to WOW your guests with wonderful and striking memories? The special event services from Russian Empire will do just that. You just tell us about your needs and we’ll try to meet your expectations! –we’ll successfully plan and manage your event, regardless of location or type.

Learn More

FIT’s

FIT’s

We don’t have fixed programs and we don’t offer identical and standard options. We can say that every new program is a work of art. The creation of every proposal is challenging and fascinating process of analysis, creation, implementation and realization.

Learn More

Leisure

Leisure

Imagine the holiday of your dreams, tell us about it and then let us do what we do best and organize your trip for you. Russian Empire DMC offers special and unique programs. Our team provides distinctive and exclusive travel experiences to all our clients and guests.

Learn More

Economy

The peasants, in addition to bearing virtually the full weight of the fiscal burden throughout Peter’s reign, were compelled to supply the state with military and civil conscripts: recruits for the army and navy and labour for the construction of fortresses, canals, ships, and St. Petersburg. Peter’s prohibition of 1723 “to sell peasants like cattle” illustrates their plight. The diminishing freedom of the rural population hindered industrial development. In addition to the lack of a free labour market, capital was in short supply and potential entrepreneurs were hard to find among the townspeople. Toward the end of the period, there were only about 170,000 townsmen, a bare 10 percent more than in 1700.

The merchants proved to be the most enterprising members of this class. Anxious to stimulate industry (as well as trade), the government took a hand in the establishment of factories but also encouraged private enterprise, especially by making up the deficiency of capital and labour. State serfs were assigned to factories, and non-dvoriane (non-nobles) received permission to acquire manpower through the purchase of villages. Of the 199 factories existing in 1725, 18 percent were textile and 31 percent metallurgical, and all but 13 had been established in the reign of Peter, half of them by the state. Most of the factories were located in the new industrial region of St. Petersburg, northeast of the new capital on the Svir, around Moscow and Tula, on the upper Don, and round Yekaterinburg. The factories eventually armed Peter’s army and navy and aided in clothing his soldiers, thus fulfilling the purpose for which they had been created. Moreover, in 1726 Russia began to export pig iron.

Relations with the West

To start the new schools and government departments, to build ships and organize workshops, and to train armies, foreigners were invited to Russia, and Russians were sent abroad. Traffic and trade with the West increased. By 1726, via St. Petersburg and Arkhangelsk, Russia imported 1.5 million rubles worth of wine, sugar, silk and woolen goods, and dyestuffs, and exported hemp, flax, sailcloth, linen, leather, tallow, and pig iron valuing over 2.5 million rubles. In 1724 a high protective tariff was imposed on all imports, to be levied in foreign currency. Russia’s commercial relations with the Netherlands and England were particularly close, but exports to Britain suffered from a break in diplomatic relations between 1719 and 1730. In a number of Western ports, Russia’s trade interests were guarded by consuls; its Eastern trading partners were Persia and China. With permanent envoys in most European capitals, Russia was able to treat war and diplomacy as a combined operation. By 1725, having defeated and made an ally of Sweden, Russia had obtained supremacy in the Baltic. Its struggle with Turkey for access to the Black Sea was drawn, but the humiliating Tatar tribute had been tacitly repudiated. United by a dynastic bond to Holstein, Russia shared with Prussia a policy of keeping Poland weak; it also was drawing closer to Austria.